CLIMB // 01 MAR 2024

FAT SENDERS

TW: Discussions of weight loss, disordered eating, and diet culture

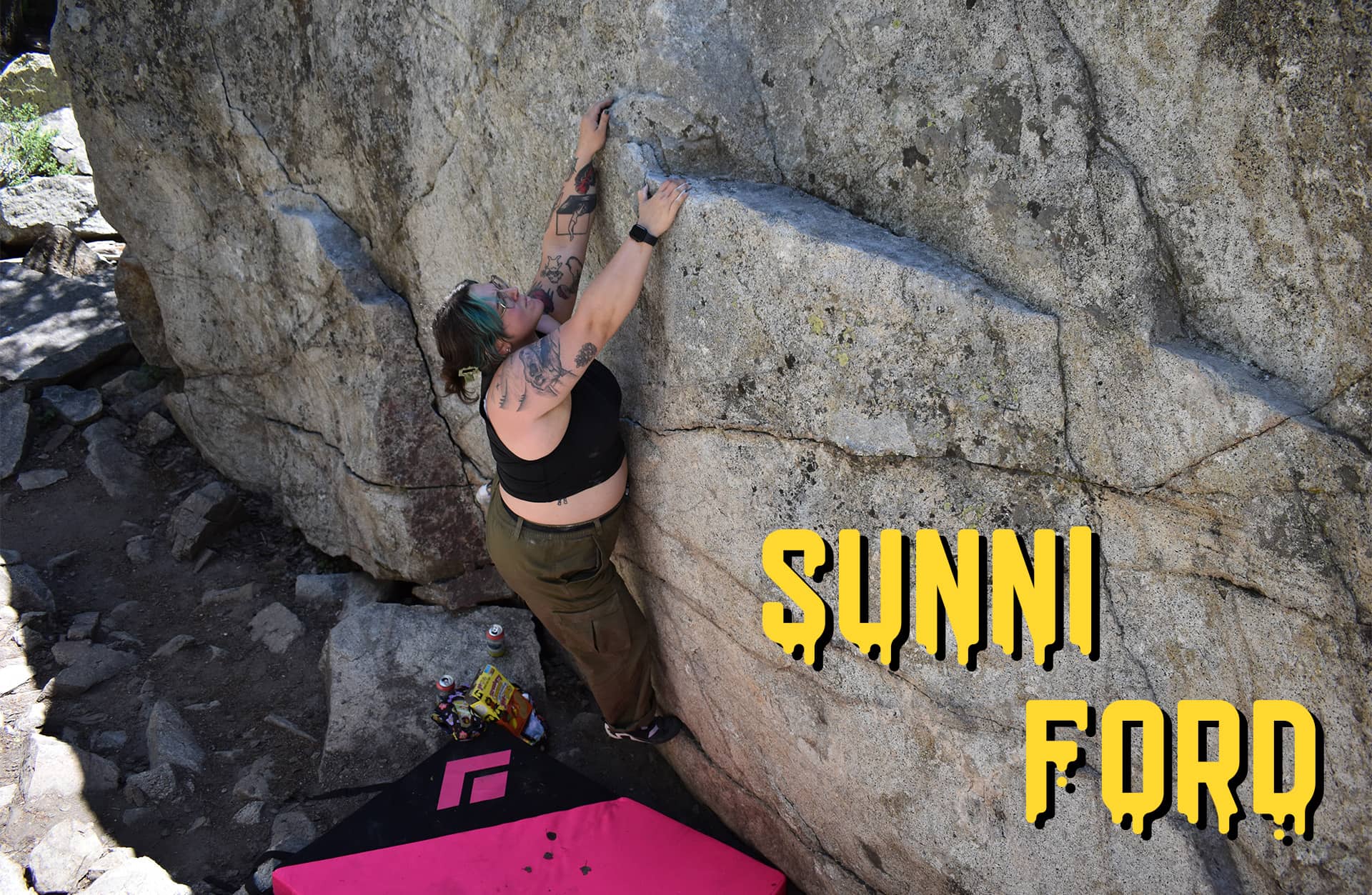

Balance, strength, patience. Essential skills for any dancer, but they also come in handy when climbing up big rock walls, as outdoorist and organizer of Fat Senders, Sunni Ford, discovered in their teens. Though, Ford quickly found out that these skills weren’t the only points of crossover between their two passions. “I started getting consistent [with climbing] when I was about fifteen. That’s when there was a lot more pressure about my body size in dance. So I needed another outlet which was a bit more accepting, which is funny now.”

Ford danced for over seven years, but it didn’t start with a deep, burning passion for dance as a kid. “Honestly, I didn’t have a lot of hobbies because I was a literal child,” laughed Ford. “My brother’s girlfriend at the time was a dance teacher.”

So, Ford joined a studio, sending them down a path of ballet and jazz competitions. It was fun. That push for constant improvement, working toward an ideal, it all scratched an itch in Ford’s brain. However, as Ford aged out of childhood into their teens, those requirements for perfection darkened.

“I think my first conversations about diet culture and weight loss happened when I was around eight years old,” said Ford. “Then once I was fifteen and transitioning onto pointe shoes [it was] ‘how much weight can you lose before we put you on pointe shoes?’”

It was these conversations that brought Ford to climbing. Their previous experiences in the rock climbing gym, at parties and such, had been fun. So, they looked to the sport as both an escape and as a way to mold their body to meet the standards set by their dance studio.

Climbing was meant to be a casual pursuit, but it didn’t take long for Ford to get fully hooked. The skills they’d honed on barre translated seamlessly onto the wall. This, in combination with Ford’s innate drive to give their passions 110% meant they progressed fast. And they only wanted to get better.

Here are just a few of the recommended searches suggested by Google when researching how to optimize climbing performance:

“What is the ideal body fat for a climber?”

“Is climbing easier if you weigh less?”

“What is the best BMI for a climber?”

Climbing is a unique sport in that it provides a concrete system through which athletes can track their progress. For many, a great deal of the satisfaction they feel while climbing comes from reaching that next level of difficulty, or “grade pushing”. That rush of accomplishment is addicting and brings people back to the wall, looking to improve at any cost. One of which is not eating.

Butter Mag is a 100% reader supported publication. By subscribing to Butter’s Patreon for as little as 2$/month, you keep Butter churning, so that together we can create a more diverse outdoor sports community.

This weight-loss crazed individual is certainly not the image that comes to mind when envisioning the climbing community. As Ford explained, “To market something to someone, you’re not going to show them the worst part. You’re not going to show them all of the eating disorder and diet talk of climbing. You’re going to show them a nice little granola community.”

Compared to dance, the more subtle nature of talks around weight in the climbing community were a welcome relief to Ford. “I subscribed to [diet talk] for so long,” they explained. “I was like, well, nobody’s on me [saying] ‘you need to lose this much weight’. People just made little comments here and there, but it wasn’t as aggressive.”

The cycle would’ve continued if Ford wasn’t forced to take a break so they could give a career in wildland fire a try. “I loved fire. I loved fire more than anything,” sighed Ford. “[First] I worked on a trail crew. After that I was like, I enjoy being outside, [what do I do next?] The person I was dating at the time then went to wildland fire, so of course I went to wildland fire.”

“I had a lot of really high expectations for myself,” they continued. “Unfortunately, I ended up in a weird spot. I had dated someone higher up and he ended up being abusive. When I got my protective order [against him, my job essentially] said, ‘okay, so are you leaving?’”

It was heartbreaking for Ford. They had fallen in love with working outdoors, but the moment they were deemed “difficult” by management, they were tossed aside. A known abuser was chosen over Ford, simply because he had more job experience. Ford was understandably devastated.

“I didn’t want to do anything,” they said. “I didn’t want to work out. I didn’t want to hike. I didn’t want to go outside. I [eventually] did realize how [wildland fire] wasn’t good for my mental health, but when that’s your whole life and career, it’s easy to come back and fall into a bout of depression.”

Soon going outside wasn’t even an option when Covid lockdowns hit. The culmination of one bad thing right after another sunk Ford to an all-time low. At rock bottom, Ford was forced to do something they hadn’t done in years: be still.

“I had never not been obsessively active,” said Ford. “I had never just eaten food. It was a big wake up call for me. I started to unpack a lot of my internalized misogyny, figure out my gender identity, and [ask myself]: what happens when I’m not thin anymore?”

Gradually, as they healed, Ford sought the joy they’d lost. It turns out it had just gotten wedged between a couple of rocks. “I’ve always loved climbing outside,” smiled Ford, recalling their cautious return to the sport. “But I took it slow. I took it really slow. I didn’t push myself [at all] in terms of grades.”

Back in nature, Ford regained a bit of their peace. Climbing transformed from an obsessive pursuit of progression, to a form of mindfulness and meditation. So when Covid restrictions lifted and Ford returned to the climbing gym, the shock of the naked judgment toward Ford’s change in appearance from other climbers jolted them. “I came back and people almost like, felt bad,” recalled Ford. “They were like, ‘your career is shot’.”

Luckily, Ford had no interest in falling back into their past trappings, choosing instead to give their body the care and respect it needed. But it did get lonely. And that was the reality Ford accepted, until one fateful road trip when an episode of Maintenance Phase introduced them to Unlikely Hikers. “I was like, how cool would it be if there was a community of people in bigger bodies that got to just hang out and climb,” smiled Ford. “But also look at the greater implications of anti-fat bias through the avenue of outdoor sports.”

That community is now known as Fat Senders. Launched in 2023, Ford has hosted events for not just climbing, but also skateboarding and skiing. The group took off with its first Instagram post, as Ford recalled, “Our local gym immediately hit me up and was like, we want to host this event. Then, I worked for Black Diamond, and they also immediately wanted to help out.”

With such high expectations from the get-go, it’s understandable that Ford was a bit anxious going into their first meet up. “I thought it would be me, my partner, and then no one else would show up. I was crying, sweating,” they laughed. “Eight people ended up coming and it was fun!”

As a consequence of Ford’s own intersectional identity of nonbinary and plus-size, Fat Senders inevitably attracted similar individuals. It’s a group that proves there’s no right way to “look trans”.

“I still struggle a lot with feeling like I belong in a community where typically what I’ve seen for [representation of] nonbinary people is white, thin, and wealthy,” explained Ford. “There’s a lot of anti-fat rhetoric in the trans community, which is sad. But seeing that intersection [at Fat Senders] has been really cool.”

Enjoying this article? Consider subscribing to our Patreon for as little as 2$/month to ensure we can keep sharing more stories like this in the future!

Running Fat Senders is just the start of Ford’s work to detangle anti-fat ideology from the world around them. From the models used to advertise a gym’s fitness classes, to lobbying with brands to use actual plus-size fit models for their plus-size gear, Ford has an extremely long to-do list. But the healing process is not linear, and sometimes all that work takes its toll.

“It’s brought up a lot of stuff for me that I still need to process,” they said. “It’s a lot of focus on bodies. When I’m doing research, reading papers and such, it can be triggering.”

“Also having conversations with brands and gyms can be really triggering. It’s hard to explain [and justify] your existence to people over and over.”

Returning to climbing and starting Fat Senders is a continuous lesson for Ford in the art of balance. Mastered once in dance, twice in climbing, they learn it now in a different form. It does not come naturally.

Ford laughed as they recalled, “My first two years of skiing, I progressed like crazy. Then my third year, I plateaued. I was like, what is happening? I have to ski everyday. I have to progress. Then it just wasn’t fun and I was like, whoops.”

Ford knows that the battles, both with the outdoors industry and their own relationship with achievement are worth the fight. It is all to create the opportunity, for anyone in any body, to fall in love with the outdoors just like Ford did. “Every year I do this thing where I’m like, I’m quitting. I’m done. And then I mosey on back into the climbing gym,” laughed Ford. “I think it’s climbing outside that keeps me coming back. It’s kind of scary. It keeps you present. I like big adventure days, even if it’s really easy climbing. It’s just free.”