CLIMB // 01 DEC 2023

ROCKING HARD SH*T

TW: detailed medical descriptions

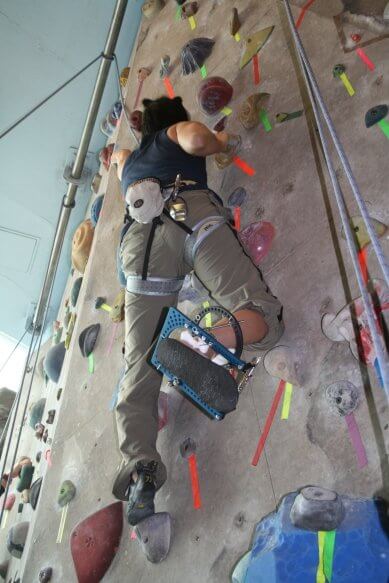

“There were like a trillion tick marks,” said adaptive climber, ski patroller, and Search and Rescue (SAR) volunteer Clara Soh. Recalling a route in Spain, she described the small chalk lines that had guided previous climbers through the climb’s most difficult section. Each tick represented a place for athletes of various heights to put their feet as they pushed through the crux.

“This guy who was working on it with me. He asked, ‘what do you do with the crux?’ I was like, you don’t want to know,” she laughed. Soh has a unique approach to her climbs since her beta uses only one leg. “He’s like, ‘no, no, I can’t figure it out.’ I was like, well, first I slide my right foot and I put my left foot here. Then I move and hop my left foot. Then I pace my right foot and I just smear it. Then I hop my left foot here.”

“He’s like, ‘that’s the stupidest beta I’ve ever heard. This is a 13B, you can’t climb it with just one leg.’ And I’m like, no, you can. It’s just a different problem.”

The child of Korean immigrants, Soh spent her early years focused on academics and helping her family adapt to a new society. It left her with little time in athletics. “I didn’t grow up playing sports at all. Like, zero,” she explained. “I played soccer for three weeks and they put me on the boys team. Then my parents said I couldn’t play anymore.”

Upon graduating college, and then subsequently returning from a term as a Peace Corps volunteer, Soh was unsure what direction to take her life. “A friend of mine from college was up at Whistler snowboarding. I went snowboarding maybe a half dozen times. She was like, ‘my sister and I have got a condo, we have an extra snowboard, just come.’ So, I went and [then] found a job at one of the sister resorts and ended up at Mammoth Mountain, which I didn’t know at the time, is next door to one of the most amazing climbing areas in the U.S. But, if you called 1-800-Mammoth, I used to answer that phone.”

Working at the call center, Soh connected and grew close with a co-worker who, once the season rolled around, invited her to go out climbing. “I made every single newbie mistake on the planet,” winced Soh. “[My friend has] a size nine foot and I have a size seven and a half. I was borrowing her shoes, and I was like, these are too tight. Then obviously we were just top roping. I left the figure eight in the rope because I was like, this shit is complicated. I don’t want to have to re-tie it. So they pulled [the rope] and the knot got stuck at the anchor, and they’re like, ‘who left the knot?’ I was like, oh, you’re welcome. I did. I actually thought I was doing people a favor. [Luckily my friend is] just such a wonderful person. She took me again and it was really fun.”

Butter Mag is a 100% reader supported publication. By subscribing to Butter’s Patreon for as little as 2$/month, you keep Butter churning, so that together we can create a more diverse outdoor sports community.

After a season at Mammoth, Soh moved to New York for graduate school, bringing her new found interest in climbing with her. “That was my first year [getting into climbing],” said Soh. “And that’s when I had my accident.”

From 2003 to 2009, Soh was in and out of the hospital having had over twenty reconstructive surgeries on her right leg. During those six years, Soh’s leg was in multiple external fixators, a surgical cast, short leg cast, and splint, making walking a challenge even with crutches. “When they took [everything] off, the bones had just grown together, but not correctly. So now my foot is turned, club footed inwards. I had a surgery to try and fix it, and my surgeon couldn’t even find the joint. It was like sawing through a femur. It’s not only fixed at 90 degrees, but it’s not fixed correctly. It’s not fixed anatomically. I have orthotics I usually wear that correct for that, but it still causes a lot of trouble, like for my hip [for example].”

Unfortunately, even with the surgeries, the question of amputation is not if, but when. Soh explained, “what’s happening now is that my leg is rotting from the inside. I actually had an amputation scheduled, which I canceled, but I asked, when will I know? And [the doctor] said, ‘oh, you’ll take a step and you’ll be three inches shorter because the bones will pulverize. And that’s the day we’ll have to take your leg off.’”

After two years of relearning her body post final surgery, Soh returned to the climbing wall. “I did it mostly because I felt like I had to exorcize that demon and get over the accident,” she said. “[Then] I was going through this horrible breakup. We were fighting over the cat, fighting over the dog, fighting over everything. [Climbing] was the only thing where I was so terrified that I didn’t have the mental space to think about anything else. I was like, wow, this is actually sort of good for me. Probably if I had seen a therapist, I would have done things more healthily, and found real coping strategies.”

Little did Soh know that her coping strategy would turn into the passion she builds her life around. Now living full time in her van, Soh spends her time as a SAR volunteer , ski patroller, and of course, hard climber. In other words, Soh is not living as an adaptive athlete, she’s thriving.

However, climbing is a sport where just an extra inch of height can often be a huge advantage, and there has been more than one time where the lack of mobility in her ankle has posed a challenge for Soh. “I wish I was a better person and [could say], oh, I can be creative,” explained Soh. “I did in the last year stop complaining about being on the shorter side. I joke that my goal height is 5’7. [But] with my ankle, it’s just mostly frustrating. I actually had a really big meltdown in Rocklands this summer because I was so frustrated that I couldn’t do something that should have been pretty easy.”

She continued, “I’m climbing low to mid 5.13, which is not to spray, but it’s more than a lot of people will ever do. I don’t feel that I’m necessarily achieving less, but there are times that it’s better to walk away from routes and say, this one’s just not for me. Especially boulders. I can’t risk a bad fall.”

These challenges on the wall are in addition to the chronic pain caused by Soh’s end stage osteoarthritis and progressive necrosis. Aside from the obvious discomfort chronic pain causes, it also drains a lot of physical and mental energy. Even if individuals learn to manage the pain without thinking much about it in their day to day, that exercise still draws and drains resources, in particular, energy.

“I hiked into the Wind River Range a couple of years ago, and I explained to my climbing partner, I can’t climb the first day because after hiking 14 miles carrying a trad rack, all our ropes, food and tent and everything, I’ll be destroyed,” said Soh. “A normal person will be fine, but I’ll be incapacitated. We got in around 1P.M. and he’s like, ‘oh, you want to run up something easy?’”

It is a struggle well known by those with invisible disabilities. From just a surface level assessment, Soh is a young, healthy, and extremely active outdoors enthusiast. So when she informs friends and climbing partners about the accommodations she needs, such as time to meditate or build energy reserves to keep her chronic pain in the green zone, there can be a bit of a cognitive dissonance. “I think if I was progressing less, if I was achieving less in the sport, people would understand more,” said Soh. “But because I have found so many adaptations, people, not that they don’t believe me, but they don’t believe me. I’m like, oh, I can’t risk that. And they’re like, ‘no, it’s fine. You got this!’ I’m like, no, you don’t understand.”

In addition to constantly establishing and re-establishing her limits as an adaptive athlete, Soh has faced pushback in the climbing community as an Asian American. Many Asian Americans, both immigrants and second-generation individuals are clumped together by American society into a single, monolithic model minority. “People [will say] that I’m not actually BIPOC, [and when] I’ve gotten scholarships I’m considered less deserving somehow because Asians are so successful, but it’s actually not true. If you look at the recent arrivals, they’re amongst the least documented and least economically successful groups in the entire United States,” explained Soh. “There’s no recognition that we have individual stories and individual cultures. One of the things that I see a lot is that we’re expected to excel in school, but not in the outdoors, which I find very frustrating.”

These expectations go beyond athletic performance. More than once in her climbing career, Soh has had other people, typically men, try and push her around. “[As an] Asian American woman, you’re not supposed to be vocal. You’re not supposed to have an opinion. Every BIPOC woman has their stereotype, right?” said Soh. “I’m supposed to be the subservient Asian woman and the minute I have an opinion it’s like I’ve disappointed someone by not fulfilling their expected stereotype, and [somehow] it’s my fault.”

The truth is, when looking at the best climbers in the world based on their 8a.nu rank, Japanese and Korean climbers fill the top spots. But with a majority of companies based in and focused on the Western market, this talent is outright ignored. When companies do diversify their talent teams, athletes tend to get shoehorned into one category.

Enjoying this article? Consider subscribing to our Patreon for as little as 2$/month to ensure we can keep sharing more stories like this in the future!

“We don’t fit into one bucket,” explained Soh. “[Companies say], ‘I have one adaptive person, I have one BIPOC person.’ We can come in all colors, sizes, and abilities. We can actually bridge all of those. The other thing that really bothers me [is that], I feel like sometimes we get our participation award for just showing up and I don’t want to be your inspiration porn. I want to be known for climbing hard. Not because I’m a woman, not because I’m BIPOC, not because I’m adaptive. [I want them to say] Clara’s out there and she was rocking some hard shit.”

Whether or not her achievements are recognized by the climbing industry, rocking hard shit is exactly what Soh plans to do. Appreciating the time she has before her amputation. “My quality of life would have been better if I had the amputation because I would no longer be in chronic pain. But there’s just not a lot of below-the-knee people who climb at a high level. I’ve lost about 80% of the feeling in my foot,” explained Soh. “So I know what it’s going to be like to lose it completely. I have about 10% of the movement that I should and in a prosthetic I’ll have zero. It will significantly limit my ability to climb.”

“The last surgery I had, they took stem cells from my hip and injected them into my leg to try and reverse the necrosis. They stopped it from spreading. They can’t reverse it. They also put in some growth hormones, like osteogenic proteins. My doctor told me he bought me ten to fifteen years. That last surgery was in 2009, so I’m in the danger zone now. I’m almost at the 15 year mark. That was a big wake up call of, hey, I actually know when things are going to get much worse. So let’s enjoy the time before that.”

This doesn’t mean Soh plans on quitting climbing post-amputation, but as she explained, “It’ll be another process of relearning a new body, and it already took me two full years to learn this body. How many more years to relearn that one? I’d like to do what I can with the body I just learned before I have to relearn another one. And I will. I’ll do that, but if I can put it off for as long as possible [I’d like to] enjoy what I have now.”

For Soh, that enjoyment means volunteering her time for various community service projects and working her way up to climbing a 5.14 graded route. “I have only just started articulating out loud because I feel like if I put it out there, I’ll also hold myself accountable for it. There’s Scarface at Smith Rock. It’s the first 14A in the U.S. bolted and sent by an American. Scarface is this overhanging and powerful [route],” she grinned. “It’s like my anti-style. If I send that one, I don’t know, it just speaks to me more. I feel like it’s more aesthetic.”

To achieve that goal, Soh is finally facing what she’d long avoided in her climbing career: training. “Hang boarding is so boring,” she laughed. “[But] I was lucky enough to be accepted to a BIPOC accelerate program where Samsara and Patagonia have been paying for the training. Samsara has been the one really pushing to get corporate sponsors to bring BIPOC athletes into the outdoors. Not just one of us, but a whole cohort of us, so we have our own community. I just finished this three month training cycle with them. I’m so close to a one arm pullup.”

“Short term goal is to get that one arm pull up locked down. Long term, I give myself two years [to climb Scarface],” said Soh. “I think it’s a real stretch goal, but that is something that I think I would just feel personally proud of. But also, a lot of it is for representation because I want to show people that you can be adaptive and still do hard things. Don’t give me a participation trophy for getting on a 5.8, which I’m not trying to denigrate. If that’s your grade that you’re at, I think that’s amazing if that’s what your ability allows and your mental interest and all the other things you have going on in your life. But I do think it’s very condescending that a lot of the industry is like, ‘oh, you did such a great job on that.’”

“Well,” she said. “Fuck off. We can do hard things, too.”

One thought on “Clara Soh”