CLIMB // 01 DEC 2022

CRIMP LABS

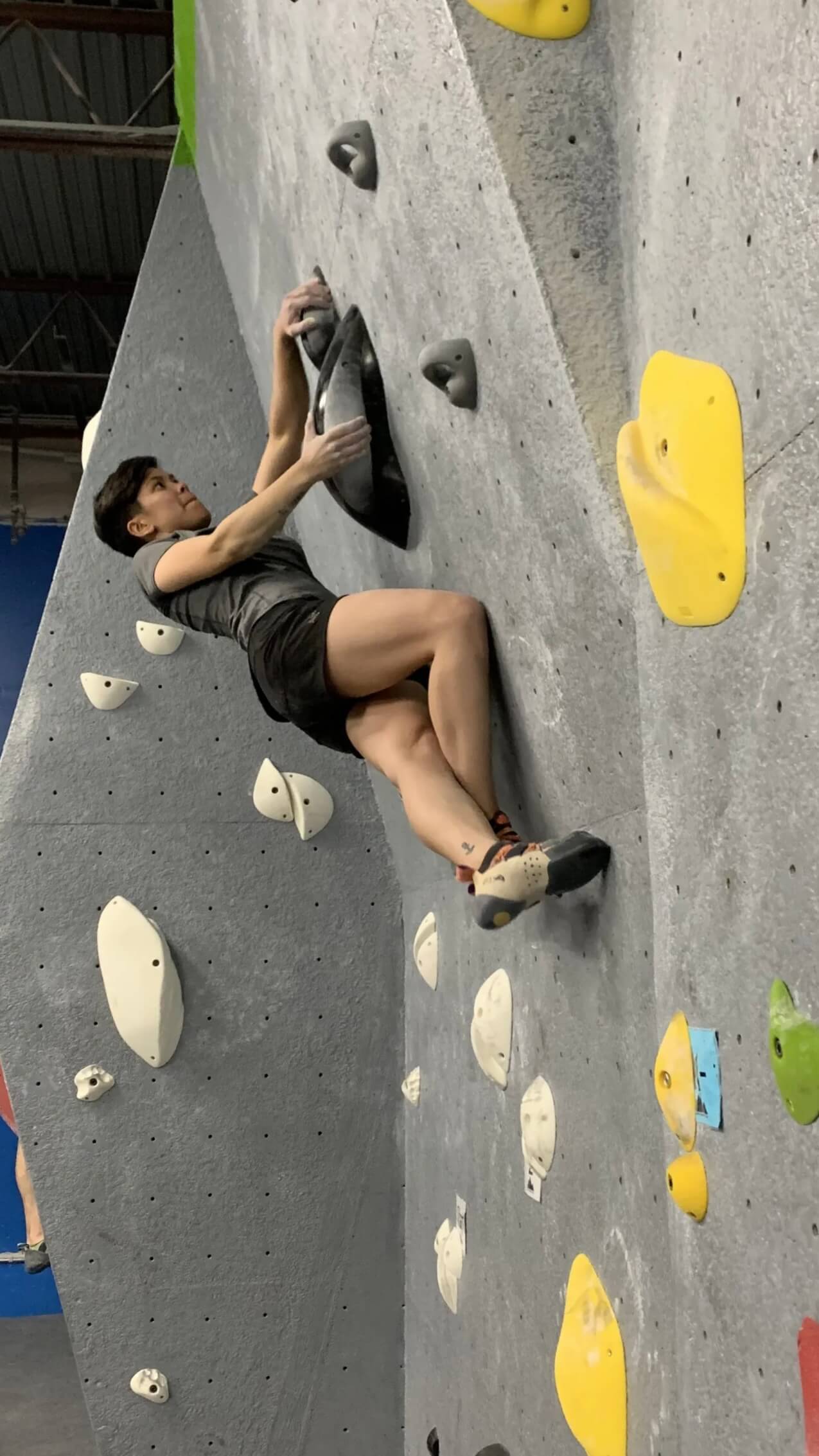

“That’s an important point that I try to find with people, the perfect balance between, okay, this is not so scary, and so hard that they’re too freaked out. It’s just the right challenge level where they’re willing to give it a shot, willing to fail and see what happens,” said Dr. Jasmin Honegger PhD, explaining her approach when coaching climbers on the wall. She gave an example of a client who’d learned the sport through traditional climbing over twenty years ago. His foundations were built around the highly technical style that trad climbing demands, and he excelled at climbs that required those movements. However, when faced with a competition style bouldering move in the gym, he struggled. Honegger smiled recalling their session together, “He tried the move and was kind of close. I gave him some cues and then the second time he just nailed it and he had the biggest smile on his face. It was one of the best moments in coaching so far.”

As the founder of Climbing Research Initiative: Movement & Performance Labs, aka CRIMP Labs, a coaching and consulting service dedicated to improving and sustaining rock climbing performance, Dr. Honegger is obsessed with movement. With a background in mechanical engineering and a PhD in biomechanics, Dr. Honegger applies her knowledge of forces present in the human body to break down climbing movement patterns. Up on the wall, a shift in weight or a slight rotation of a body segment can transform a challenging move into a non-issue. It’s in these details where Dr. Honegger thrives.

Investigating movement from the day she could walk, Dr. Honegger spent her childhood exploring the evergreen forest that surrounded her home in North Carolina. “I would go outside and climb trees and pretend that I was an explorer in the woods,” she smiled. “I think being outside [a lot] really drew me to extreme sports. I was always curious as a kid. Naturally, when you’re curious, it pulls you to the more extreme sports because you wonder, oh, well, how do people do these crazy things? Maybe I should try.”

Later moving to Louisiana, Dr. Honegger has fond memories of joining up with the other neighborhood kids to run around and play. “You could probably name any wheeled object, and we were into it,” she laughed. “I got into skateboarding and thought it was so cool. Not only that, but I think learning tricks and skateboarding is pretty hard, and I have the kind of personality and brain where if I can’t get something quickly, I get really excited to keep at it. Which obviously ties into climbing as well.”

Rolling around through middle school and even traveling to California in high school to give surfing a try, Dr. Honegger was always finding new ways to have fun outside. Then in her senior year of college at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, she discovered climbing. With an average rise of 100 feet above sea level, Louisiana is not a state known for its abundant climbing routes. But, there was a gym. “I knew this rock climbing gym as the place kids went for birthday parties,” laughed Dr. Honegger. “I had some friends who one day wanted to do something different, and someone brought up the idea of trying out the climbing gym. I liked it. It was a new way of pushing myself and trying something hard, mentally and physically. I started to realize, oh, this is something I think I could really get into. I was definitely hooked.”

Concurrently, Dr. Honegger discovered her academic passion in biomechanics. When she started her undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering, Dr. Honegger had no intention of pursuing a PhD. “I chose [mechanical engineering] because I was good at science and math and liked working with my hands. It suited my strengths,” she explained. “I really did enjoy the classes and what I was learning in school, but I did a couple of internships in different areas of mechanical engineering, and I wasn’t super interested in them. It was one of those things where I was good at what I was doing. I had the right skills, but I wasn’t motivated.”

Though uninspired, Dr. Honegger planned to graduate, find a job, and “wing it”. Even if she wasn’t enthralled by the practical work she’d done so far, being an engineer, and a good engineer at that, would open a lot of doors for Dr. Honegger to find the field she wanted to pursue.

Luckily, her answer came before graduation. In her penultimate semester, a new professor with a background in biomedical engineering came to the University of Louisiana. Dr. Honegger was able to take a pilot course and as she explained, “When I started learning how to apply everything that I had learned so far in terms of mechanics and mechanical engineering and how to translate that to the human body. That’s when I got super excited.”

From this first class, Dr. Honegger knew biomedical engineering was her path forward. Wanting to do something cutting edge in the field and always down for a challenge, she decided to enroll at the Colorado School of Mines to get her PhD.

Relocating to Colorado opened up a whole new world of climbing for Dr. Honegger and she embraced it. Pre-move, she prepped for the multitude of outdoor routes by taking a lead climbing class. “I honestly just trusted this random person, which is kind of funny,” laughed Dr. Honegger, referencing a conversation with an employee at a local gear shop. “But, she said that it would help me in climbing outside. I’d never climbed outside before. It sounded super cool. So, I learned all of those skills, how to sport lead, build an anchor, rappel, all that good stuff.”

With more opportunities available Dr. Honegger started climbing regularly as a way to decompress, especially as she dug deeper into her research. Focused on computationally modeling the way lower limb amputation might influence movement and its effects on tissue-level load in the lower spine for her dissertation, it didn’t occur to Dr. Honegger to merge her knowledge about the human body with climbing. The wall served as a place of refuge. No science allowed.

Post-dissertation, Dr. Honegger was looking for a new challenge and took a job abroad in the Netherlands. Transitioning from a PhD schedule to a standard nine to five, Dr. Honegger had a lot more freetime, so she climbed. “I specifically chose an apartment that was really close to the climbing gym that I could bike to. Of course, I had to plan that out,” she laughed. “I was climbing all the time and was starting to get into training because I’d never explicitly trained before and was seeing improvement. I was getting better.”

When she came home for Christmas after three months abroad, Dr. Honegger was feeling a little homesick and disenchanted with her job. It wasn’t until she was chatting with friends that an epiphany struck her. She asked herself, “Why don’t I just apply the skills that I have in biomechanics to climbing? Because I’m really excited about biomechanics and human movement and understanding how we move. I’m also really psyched on climbing, this interesting, unique sport that we have. How did I never think about this before?”

On the plane ride back to the Netherlands, Dr. Honegger began to brainstorm what would eventually become CRIMP Labs. With a full year contract to finish out abroad, she had plenty of time to ideate and hone in on what she wanted CRIMP Labs to be. “I knew from that moment on,” she said. “That if I didn’t set forth and at least try to pursue [CRIMP Labs], I would deeply regret it.”

Now just shy of a year since launching, CRIMP Labs has attracted a number of clients for both in-person and online coaching. In her sessions, Dr. Honegger focuses on expanding and refining climbers’ movement libraries so they can confidently approach any route. A climber’s movement library is the accumulation of techniques they’ve learned in their time with the sport. A diverse movement library allows climbers to adapt to problems instead of becoming stuck in habitualized, suboptimal patterns.

How someone learns to climb establishes how they will tackle routes of any style, as was demonstrated by Dr. Honegger’s trad climbing client. “Honestly, when he first asked to be coached by me, I thought, well, I don’t know if I’m your person,” she laughed. “But [he wanted my coaching] because he recognized that I can help people unlearn bad movement habits. Sometimes I try to get him to do coordination moves on slab or comp style boulder problems that are nothing like scary trad [climbing]. What I expressed to him is that by building these skills, that are seemingly outside of what he would experience in sport climbing, is that they create this really robust base for his movement library where he has different books and chapters to choose from in terms of his movements.”

By breaking her clients out of their self-imposed limitations, Dr. Honegger has watched their abilities and confidence skyrocket. There’s a new willingness to approach problems that might be outside their comfort zone. As she explained, “That confidence off of the wall, that is so important, because so many climbers [if a route is their] anti-style [will] think, I’m bad at slab, or I’m really bad on slopers, or whatever it is. Immediately you just shut yourself down because you don’t have that off the wall confidence. Once you say, oh I’m bad at this, you are ingraining that idea in your brain and it’s limiting your beliefs and if the belief is not there, your body’s not going to do it. They have to go hand in hand.”

Though the work she does with clients is a type of training, Dr. Honegger’s goal is to teach climbers how to listen to their bodies, not necessarily focusing on isolated strength exercises. “I feel like the climbing world, especially on social media, is really training obsessed right now,” she explained. “It is important to be strong. I want to be explicit about that. It’s just realizing that climbing is so complex, [so your training has to be varied] and that’s probably why a lot of people are interested in [climbing]. It’s such a strange sport. You can be the strongest climber out there but lack improvement and plateau without good movement and coordination.”

Along with meeting with clients, Dr. Honegger shares climbing movement analysis on Instagram. Breaking down moves from climbing competitions, her insights provide her followers new tools to bring to the wall to improve their own sessions. Even these bite-sized lessons have a great impact, and the response to the CRIMP Labs page shows it. “[I’ve been] quite surprised at [all] of the positive messages I get,” Dr. Honegger smiled. “People reach out to me and randomly say, I really love what you do!”

For Dr. Honegger, CRIMP Labs was a bit of an experiment. As with any new venture, there’s been a few pivots along the way, but overall she couldn’t be more pleased with how her vision has grown. Though her primary focus for now is to stick to the status quo and gain more traction, Dr. Honegger dreams of one day setting up a specialized center for CRIMP Labs, or if you will, a lab. “An actual lab for CRIMP Labs is something that I would be really excited about. People could travel and visit me in the center and we could play with different sensors and devices and start to get even more nerdy for people who are into that,” she grinned.

Through this intersection between her love of climbing and science, Dr. Honegger has revealed many a climber’s potential. Whether it’s celebrating the little victory’s with clients, or connecting with other athlete’s online, she is grateful to be able to share her passion with the world. “The fact that people really enjoy and appreciate the nerdy information and all of those micro details on climbing movements [is exciting],” she grinned. “I had no idea that climbers would be so interested in how nerdy I could get about climbing.”

In retrospect, it seems obvious to Dr. Honegger that she would bring climbing and biomechanics together, putting science in motion. It was almost by unconscious necessity that she formed the mental schism between her climbing and research. Doing so allowed her to build both skill sets independently, so when they did come together, they could form something great. “I think they were separate when they needed to be separate,” she explained. “And then all of a sudden, everything clicked.”