SURF // 01 MAR 2023

COASTAL QUEER ALLIANCE

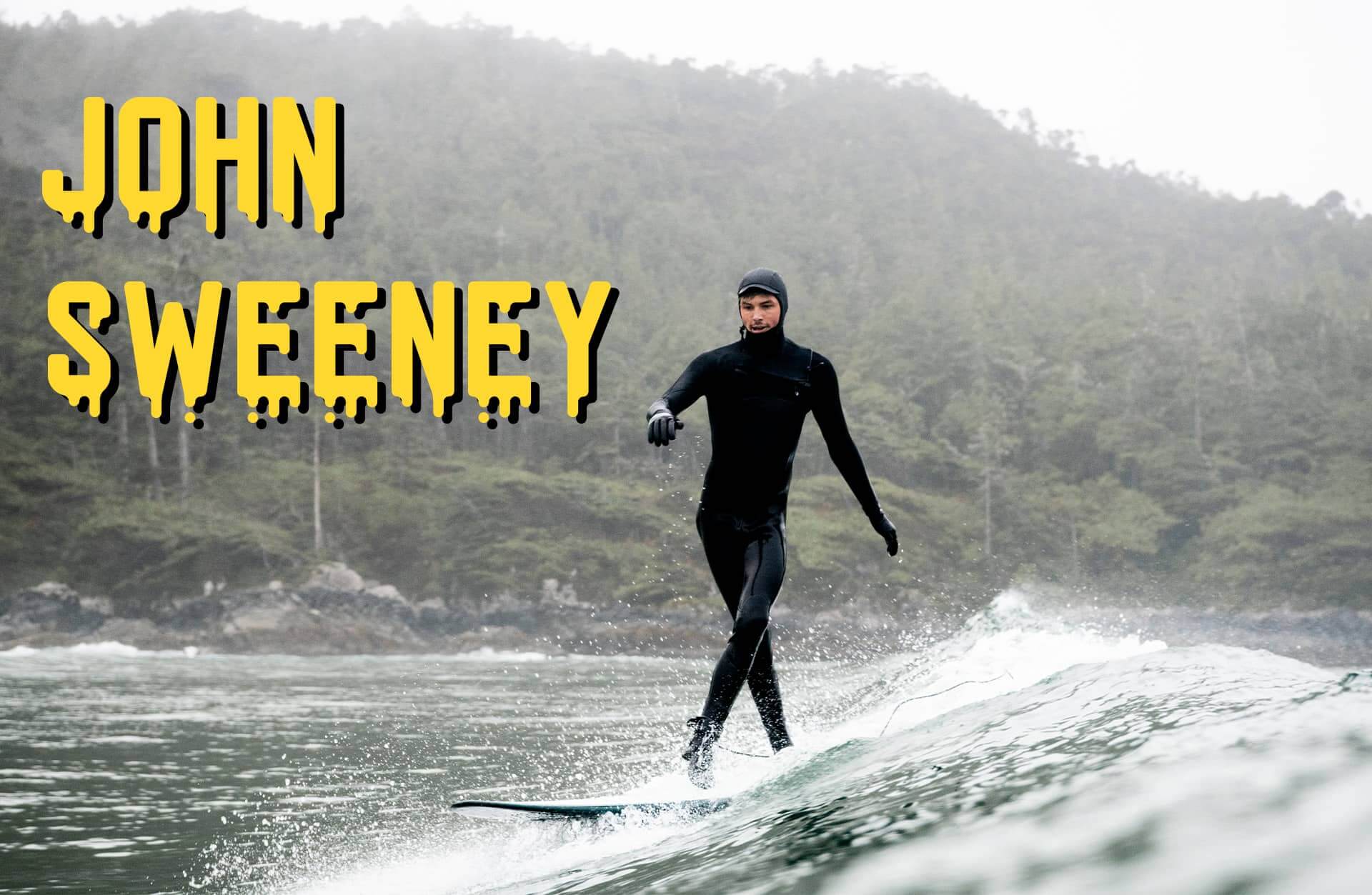

“I carry a lot of privileges that fit the stereotypical surfer archetype. I’m white, I’m blonde, I can present as masculine as I feel or need to, and those things will get you to where you need to go as a surfer,” reflected John Sweeney on his past experiences in the water. Even before co-founding Queer Surf Alliance, a non-profit organization committed to bolstering the queer community in and out of the waters of Tofino, British Columbia [Tla-o-qui-aht Territory], Sweeney had no interest in assimilating with the toxic masculine norms of surfing. However, it was hard not to let those fears of how he would be perceived impact Sweeney’s time in the water. “I feel like I would go out there and hold this energy in defensiveness because of [the more aggressive] people in the water. It rubs off on you and you feel like you have to sink to that level in order to be accepted or to feel like you can be there. But not everyone is able to just hide [their queerness] and nobody should ever have to. It definitely puts a bad taste in your mouth when you’re trying to do something that you love.”

Raised in the landlocked province Saskatchewan, Canada, Sweeney didn’t take the direct path to surfing. “It’s a patchwork beginning to getting introduced to the sport, for sure,” Sweeney laughed. Though the closest ocean was over a twenty four hour drive away, the one hundred thousand lakes in Saskatchewan meant that he still grew up a water baby. “My parents had a boat and they’d take us out tubing, wakeboarding, and waterskiing. All those fun lake activities. I became pretty comfortable with being in the water and wiping out. [I got] used to the speed and using water as a medium to have fun.”

At the same time, in high school Sweeney dug into the world of surf clips and movies, fascinated by the sport. “I always pretended to be surfing when I was on a paddle board or my little skim board or whatever,” he smiled. “ Learning how to wakeboard led to wakesurfing, and the feeling of what it’s like to be propelled by the water on a very small board. When doing that, I was like, oh, yeah, this really makes me feel like a surfer and I can’t wait to do this in the ocean someday.”

Exploring surf media as a queer teen can be discouraging, but for Sweeney the 2014 documentary OUT in the Line Up served as a source of reassurement and confirmation that he belonged in the surf community. “[OUT in the Line Up] made me really feel like I could do it, you know,” he smiled. “From the beginning it put the idea at ease that just because I’m gay, I’m not good at sports or that I don’t want to do them. I was like, oh, well, [queer] people have been doing this. I think that’s something that I want to do as well. I found it super inspiring.”

In high school when he had the opportunity to join a youth trip down to California, Sweeney wasted no time packing his bags and jumping on the bus. Exploring all the Golden Coast had to offer, the group traveled to theme parks, landmarks, and of course spent a day learning to surf. As he practiced in the safety of the white wash, Sweeney was able to channel his years of practice on the lake and catch the ocean waves that filled his dreams. One of the instructors took note of Sweeney’s enthusiasm and pulled out some extra gear, so the stoked teen could continue to surf during the group’s second time slot. “That was really affirming for me,” smiled Sweeney. “After that, I was just like, yeah, I want to learn this. I just have to figure out how because I live in the middle of the flatland.”

Post graduation Sweeney left the flatland for Central America. Bopping around between beach towns, he rented boards and committed himself to learning the sport. After returning from his travels, Sweeney moved to Vancouver for beauty school where he trained to become a hairstylist. Still needing to scratch that surfing itch, he made a trip out to Tofino where he stumbled across the cold water surf scene. “I really liked it out there,” he explained. “I was fascinated with the idea that you could surf in Canada.”

Plans were brewing and Sweeney was set on moving to Tofino to chase the surf, but underneath his fervor, something nagged at the back of his mind. He was never alone on his board because with every wave he caught he carried the fear of remonstrance. “I don’t think I was ever trying to not be queer or ashamed of being queer,” he explained. “But it was definitely a lot more subdued. I was like, oh, I can be this kind of queer person. I can be this more palatable queer person to all my other straight surfer friends. [I felt like it made] me special that I’m gay because it set me apart from the rest of the straight surfer friends.”

It wasn’t until after a year of living in Tofino, when Sweeney’s childhood friend and fellow Coastal Queers Co-Founder Sully Rogalski (they/them) made the town their home as well, that he was able to digest and dissect his feelings.

The duo’s friendship predates memory with their first playdate arranged before they even entered school. Together through every grade and living right across the park from one another, they seemed destined to become best friends. But there was another layer as Sweeney explained, “I feel like what made us a really good pair and probably what made us really good friends was that from the beginning we were challenging. Critically thinking from a young age about what we were being told and the rules that were set out for us and not really taking no for an answer all the time. I think we really bonded over that shared experience of asking ‘why?’”

From grade school petitions to expand rules around recess, to changing the regulations around Senior Presidency during their time on student council in high school, Sweeney and Rogalski were always looking for places where they could make a positive change. So when the pair reconnected in Tofino, an evolutionary enterprise was imminent.

Huddled together in their two camper trailers for the winter of 2020, Sweeney and Rogalski had plenty of time to chat about their new community. What was immediately apparent, was the lack of a visible queer community. “We noticed that there were no signs of queer people anywhere. We didn’t seem to notice queer people out and about. We didn’t see any rainbow flags. No signs of queer inclusivity.” For Sweeney who had moved from Vancouver and Rogalski who’d moved from Toronto, this was a bit of a shock. “I think we took our queer community for granted [in highschool and beyond] because we just became friends with people who were queer before we all knew that we were queer.”

At the same time, the pair began to deconstruct Sweeney’s concerns around surfing. He explained, “I was starting to tune-in more to the history of surfing and the ways that it’s so problematic in our current society. I was also paying more attention to the queer surf groups that were happening in other places. I found them really inspiring because [they’re able to] hold surfing as this awesome thing that [they’re] super excited about, [with the intention of helping the surf community] get better and better.”

Tucked away from the rainy weather in their trailers, they began to scheme. “[We started] to think about what was missing, what needed to happen, and how we were going to [make that happen],” said Sweeney. As they compiled their list, two needs in particular stood out to Sweeney and Rogalski: community and healthcare.

Sitting two hours away from the next closest hospital, Tofino’s medical centers are the primary health services for both the town itself and several surrounding towns and Indigenous communities. Overextended by serving a large community and with limited resources, the hospital lacks pre-established pathways to queer health services one may find in larger cities. “You have to have full autonomy over your health,” explained Sweeney, drawing from his own experiences with Tofino’s healthcare system. “Knowing what you need, knowing what you want, knowing what is available to you, and then bringing that to your physicians. It’s tough. It shouldn’t have to be like that.”

The more questions they asked, the more Sweeney and Rogalski wondered if there were other people in Tofino with similar thoughts. Collecting their ideas, they organized a community Zoom meeting in the spring of 2021 to hear what other folks in the Tofino area thought. Sweeney was surprised by the variety of individuals who attended that initial meeting. There were of course other LGBTQIA+ folks, but local business owners and parents of queer children also gathered in this online meeting. They all had the same desire, to create more queer support in Tofino. Encouraged by this initial meeting, Sweeney and Rogalski set to work, and Coastal Queer Alliance was born.

Joined by their third co-founder Andrea McQuade (she/her), who has worked in public relations for several years at the non-profit Clayoquot Cleanup, the trio was able to quickly register Coastal Queer Alliance as a non-profit in May 2021. Their first priority was to enlighten people about the queer community in Tofino, and what better way is there to bring people together in a surf town than to surf? As Sweeney explained, “People are going to come here to surf. Queer people are going to come here and want to have [that surf] experience. [Rogalski and I] came out here as queer people years ago and we surfed. We paid a lot of money to rent the gear and we hauled it all down to the beach, an hour each way. It was fun, we loved every second of it. But had there been a group, had we seen a poster or something saying, ‘hey, there’s a Queer Surf. You can get your rentals, your gear, your surfboard, your lessons, your transportation, and it’s all free and you get to hang out with queer people.’ That would have been fucking awesome.

With the support of the local women lead surf school, Surf Sister, that’s exactly what Coastal Queer Alliance did. With support right off the bat, Coastal Queer Alliance was able to host several Queer Surfs over the summer of 2021. “Our first season was pretty successful. We had a few good turnouts. It was a lot more casual,” said Sweeney. “Show up to this beach, we’ll give you a surfboard and a wetsuit, Surf Sister will give us a little lesson, and then we will go out. It was great.”

Along with their Queer Surf events, the group organized several Queer Skates and an Art in the Park meetup. During this pilot year of events, the group was able to bring out several surf photographers to capture the group’s success. At the same time, Sweeney and Rogalski mentally noted what worked at their events and what needed improvement. All this preparation came to a head in the winter, when it was time to apply for the next season’s grants.

Using the power of community as a foundation, Sweeney, Rogalski, and McQuade were able to pursue the ultimate goal of Coastal Queer Alliance, to create a non-profit rooted in collective care that can support the queer community and beyond in Tofino. In 2022, the group was able to tackle the next branch of their plan, healthcare.

Over the last year, the group has created several guides for various queer health services in an effort to simplify and clarify the process. It is easy to get trapped in a cycle of referrals and tests in which a patient can quickly be thrown back to the beginning by a missed appointment. By providing a checklist of sorts, folks are able to go to their appointments with more autonomy over their health without the mental labor of hours of research.

As Sweeney explained, “If we can say, ‘hey, look, these are the steps that you can take to receive this [care]. We’ve talked with these people and these are the recommendations.’ It will help make things easier in the short term. Then we can work on longer term solutions that take longer timelines and bigger budgets. But as a small organization, what we can do for the people who come to the community, to live the lifestyle that we want to be living, is to supply these short term solutions that can help guide them to where they need to go.”

In tandem with working on their healthcare resources, Coastal Queer Alliance doubled down on their plans for Queer Surf. “Sully is an amazing planner,” smiled Sweeney. “They are so organized and in touch with everybody. They built a structure as to how [Queer Surf] would go down each time. We were able to put on five Queer Surfs over the 2022 season, and they went seamlessly. We had great turnouts. Our kickoff event had so many people. Surf Sisters was able to bring out enough instructors so that we could have three separate groups: beginner, intermediate, and more advanced. Different people who could teach different tips and tricks. There was really truly something for everybody there.”

This notion was reinforced by the feedback the group received from attendees. Hosting a post-surf hangout at a local beach-side grill, Coastal Queer Alliance was able to gather everyone’s input. They used that information to better address people’s needs and create better events. The responses were heartwarming. “A lot of people were like, ‘I didn’t know that there were so many queer people in Tofino or we want to surf for longer next time’,” smiled Sweeney. “It was really cool to hear that because people weren’t having that same struggle [of feeling like they don’t belong] from the beginning. They felt safe and wanted to do it again. They continued to go out, bought gear on their own or sometimes went out [independently] with people that they met at Queer Surf. It’s really cool to see [Queer Surf] have that impact on people and have people get in the water who might not have done it in the first place. Just eradicating that negative experience of queer-phobic surf culture.”

Going into the 2023 season, Rogalski’s wall is already filled with post-it notes of plans and ideas. With all they’ve accomplished, it’s easy to forget that Coastal Queer Alliance is run by just three people. In an effort to lighten some of the load, the group hopes to bring more people onto their team. By diversifying insights and skill sets, there lies the opportunity to tackle even bigger projects in future years.

For Queer Surf in particular, the team wants to incorporate more classroom style events. For example, teaching surf etiquette in a way that negates the current competitive interpretation. “We’re all going to make mistakes, accidents happen,” said Sweeney. “But a harm reduction approach to surfing [means newer surfers] don’t have to learn the hard way. Going out there, not knowing anything and getting into situations [that put themselves and others at risk].”

Finally, to integrate more into the Tofino community as a whole, Coastal Queer Alliance plans to put together a workshop for businesses and organizations in the area. With the growth of local support for the queer community, a crash course would be able to answer a majority of the questions the group receives. It’s a simple way to expand awareness without inundating their inbox.

A key part of this education is expanding people’s pre-existing conceptions on how to support the queer community. One example being that pride is not the zenith of queer events. “We’re like, pride is a massive party okay?” laughed Sweeney. “We have other things that we want to do. We had a whole day long event with a queer market, a community meeting, access to harm reduction supplies, and queer musicians, but people [outside of the queer community] still have this idea of what they want [queer support] to be. So we’re saying, look, these are the things that the queer community actually prioritizes and needs. We don’t need to waste our money on a parade when we can put all of these resources into events that we decided we wanted.”

It is through these patient conversations that Coastal Queer Alliance embodies one of their key values, growth. As summarized on their website, “We believe growth occurs at the intersection of education and empathy, and it is integral that we normalize and encourage the ability to change our minds after being presented with new information.” It is with this belief, combined with the lenses of critical thinking and accountability, that Coastal Queer Alliance approaches every step of their organization.

Sweeney expanded, “[We have to ask ourselves], how do we engage and interact with ideas that make us uncomfortable? I [think that idea] can really be applied to surfing and surf culture because otherwise what’s the point? Where’s the substance if you’re not going to analyze it and let it teach you so you can grow?”

“[Surfing] could be a way more interesting sport,” he continued. “There’s so much more substance there than you might think. You can be scared of it and run away from it. Or you can become even more passionate about it because you realize how many different ways you can adapt, grow, and learn because of this sport that you love. It’s a really unique and interesting place to be. I feel like it’s what keeps me reinspired over and over again. That’s the perfect recipe for growth.”

Community organization has long been a part of queer history. From big movements like the Chicago Society for Human Rights, to the growing number of specialized queer groups in the outdoor community, each viewed their goals through a queer lens. A lens that asks, how can we adapt in a way that benefits everyone? For Sweeney, reinterpreting surf culture through this new perspective has been one of the biggest personal impacts of running Coastal Queer Alliance.

“The swell is going to be doing something different every day. The wind, the tide, which surfboard you choose, which break you’re at, it’s all going to be different every single time,” explained Sweeney. “So why are we trying to force ourselves into all of these boxes [of what we idealize surfing to be] when we can recreate things to work to our advantage. So we can all have fun? [Coastal Queer Alliance] has really changed my perspective on surf culture, what it looks like, and what it can look like in the future.”

For Coastal Queer Alliance, they want that future to be a place where every queer person feels welcome on the beach, even if they don’t surf. “At Queer Surf, we’re really open about that,” said Sweeney. “You can come here and make a sandcastle if you want. You can hang out, sit on the beach and cheer people on. You can go for a dip, get in your wetsuit, flippers, and bodyboard. You can come and do whatever you want.” Because, at the end of the day, Coastal Queer Alliance’s goal isn’t just to create more queer surfers. It’s to provide resources and opportunities for connection to a previously fragmented community.

Still, as a surfer, Sweeney can’t help but smile as he reflects back on the past two years of paddling out to the line up, surrounded by people with whom he could fully be himself. Thinking back on all he, Rogalski, and McQuade have accomplished, Sweeney grinned, “I think Queer Surf has had a very big splash, which is pretty awesome.”